- Home

- Robert Cham Gilman

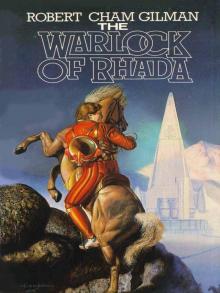

The Warlock of Rhada

The Warlock of Rhada Read online

THE WARLOCK OF RHADA

Robert Cham Gilman

The first book in the Rhada series

Copyright © 1985 by Robert Cham Gilman. Cover art by Kevin Johnson. All rights reserved.

An Ace Science Fiction Book. Published by arrangement with the author

ISBN: 0-441-87310-3

Chapter One

Of his youth in the last of the Dark Time, St. Emeric of Rhada wrote: “I suspected, but did not know with certainty, that Glamiss was born to conquer. We rode together on Ulm of Vara-Vyka’s business as simple arms-brothers, and we spoke of God in the Star, and of politics, of course. Have I not said we were young? And do the young not feel sure they know what is best for all men? But it was The Warlock of Rhada who taught us the long reach of Destiny.”

This reference to a “Warlock of Rhada” in Ulm’s fief on Vyka, parsecs from Rhada, has puzzled scholars for almost thirty centuries. It appears in St. Emeric’s Commentaries, written when the great Navigator was a very old man. Who was this Warlock who taught saint-and conqueror-to-be about the “long reach of Destiny?” We do not know. Early chroniclers tell us that Emeric, by birth a Rhadan noble, struggled all his life against “the sin of arrogance and pride.” We know that his presence on Vyka, and his position as military chaplain to the warband of Ulm of Vara was a punishment for some infraction of the Way. The Grand Master Talvas Hu Chien had removed Emeric from command of his starship and--the phrase is still used among Navigators--had “put him on horseback” to teach him humility.

In the fall of the Standard Year 3946 GE (the exact date is uncertain) Nav Emeric accompanied Warleader Glamiss (a bonded mercenary at that time, though Vykan by birth) on a punitive expedition of some kind into the Varangian Mountains (the name dates from a later period--in 3946 the mountains were uncharted). It was there, apparently, they encountered the mysterious Warlock--and having done so, went forth from that place to change the history of man in the galaxy.

--Nav (Bishop) Julianus Mullerium The Life of St. Emeric,

Middle Second Stellar Empire period

In that Dark Age men imagined that the Great Sky was but a thousand kilometers above them. The crumbled remnants of the First Empire lay scattered like dust across the galaxy. Unity was a concept unknown. There was only the Order of Navigators, the worship of God in the Star, and a million bandit chieftains on a thousand worlds of wilderness. There was little history and less law. The warmen ruled by the strength of their arms and the sharpness of their iron.

Such was Glamiss’s time.

--Vulk Varinius (Academician of the Council of Ministers, 625-870 New Galactic Era),

The Vykan Galactons, Middle Confederate period

The troop had been traveling since dawn: fifty warmen, a Vulk, and a priest Navigator. For a dozen kilometers they had followed the river coursing down from the unknown mountains, but for the last hour they had angled away from the tumbling water, traversing the rocky slope toward the crest of the ridge that formed the last natural obstacle between them and the valley of Trama-Vyka. The horses, all war mares, grumbled as they padded over granite and shale; the warmen were silent, for they were Glamiss’s men and well-disciplined. Harnesses jingled softly and the harsh light of the Vyka sun shone through the feathery conifers and dappled the steep hillside.

The troopers were armed in the manner of the Vara-Vykans, dressed in shirts of chain mail, their legs booted or wrapped in weyr skin buskirs, swords slung across their backs with the hilt at the left shoulder. The Varan pennons hung limply from their lances in the still mountain air; the white sunlight was hot on their furred and surcoated shoulders.

When the two lead riders reached the crest of the ridge, the warleader raised his hand to signal a halt. “There it is,” he said to the cowled and mailed priest-Navigator at his side.

At their feet the rebel valley stretched away in rising terraces toward the northern mountains, white with snow and the melting glaciers. A cool breeze rose from the land below and ruffled the fur edging on the warleader’s cape. The mares muttered to one another in their guttural Rhadan dialect and clawed at the rocky ground.

Emeric Aulus Kevin Kiersson-Rhad, priest and Father of the Holy Order of Navigators, eased himself in the saddle and studied the valley of Trama. It did not look damned, yet it well might be. The Order had heard tales of warlockry in the rebel valley. Emeric was here, armed with all the awesome spiritual powers of the Holy Inquisition. The red fist sewn on the cowl of his habit proclaimed it. Behind that crude symbol stood all the righteous powers of the Order: a thousand starships and the moral sanction of the Grand Master himself. Once Glamiss’s small troop established itself within the valley, Emeric the Navigator would hold the power of life or painful death over all its inhabitants.

It was a beautiful valley, Emeric thought. Not the sort of place where one would expect to find sin and abominations. Nearby, the slope fell steeply away into a talus of silvery gray rocks and fleshy brush, green leaves veined with amber. Several hundred feet below the talus, whose face gleamed with quartz and metal ores, the forest of tall and feathery conifers began once more, and beyond that the river, its course gentler here, twisted and curved gracefully through broad and fertile meadows of mountain grasses.

But dotting the meadows Emeric could see bare trees, their woven branches reaching high into the cool air, and in the highest branches, great eagles nested. He murmured an Ave Stella. He had heard dark stories of the eagles of Trama. Their armored heads glinted in the sunlight, and from time to time one would spread its wide pinions and cry out. At this distance the shrieks were faint, but they had an almost human quality that raised the hackles on the back of the priest’s neck, for it was said the animals of the valley of Trama were bewitched, that they contained the damned souls of some of the most wicked of the Old People.

Even as he watched, some of the great birds took flight. The light of the Vyka sun glittered on the talons, on the tips of the wings, and on the outthrust feet. Emeric’s mare, a roan called Sea Wind, danced beneath him, baring her teeth and stretching her own fighting talons at the sight of the rising birds.

Glamiss said, “Can there really be weyr flocks enough here to feed both the warband and those eagles?”

It was the withholding of weyr-tribute that brought Lord Ulm’s warmen into the valley. To withhold what was due the lord was rebellion and must be punished.

The first year that the Tramans did not send their tribute, Ulm had been too busy elsewhere to take action against them. The second year the Order of Navigators became involved. Local priests had heard rumors of witchcraft in the valley and had reported it to the Bishop. And now, finally, three years after the first act of defiance by the weyr-herders of Trama, here was a column of Lord Ulm’s warmen and a priest-Navigator to represent the Holy Inquisition.

To carry the Red Fist of the Inquisition into a relatively harmless village of herdsmen was not an assignment pleasing to a highborn lord Nav, a descendant of princes. But like it or not, Emeric Aulus Kiersson-Rhad, priest and pilot of the Order of Navigators, had orders to investigate Trama for warlockry, witchcraft, or for any evidence of worship of the two Adversaries, Sin and Cyb. If he discovered these abominations, he was empowered by the Grand Master of Navigators to burn miscreants and blasphemers.

The religious mission was a punishment, Emeric realized. His ecclesiastical superiors thought him too ready to question, too proud of his birth, too ambitious to wait for advancement in the Order’s good time.

“Whatever there is in this valley, there will be less when we pick it clean for Ulm and the Inquisition,” Emeric said heavily.

Glamiss gave him an amused look and said ironically, “That isn’t the remark of a starborn lord

and priest, Emeric. What will become of us poor mercenaries if the nobility starts developing a conscience?”

There was always a slight edge between them. Emeric was, indeed, starborn--the cousin of Rhadan kings. Glamiss, on the other hand, was a common man, a mercenary, dependent for his future on his sword arm.

Glamiss said, less ironically, “I was born in a village not unlike this one, Emeric. We were cold, poor, and hungry. We were lucky if we saw a priest once in three years. If folk slip into the worship of devils, of Sin and Cyb, can you blame them?”

Emeric studied his friend soberly. “It is for asking questions like that that I am here, Glamiss, on horseback, instead of piloting my own starship through the Great Sky. Men manage to create their own devils no matter where they are, or how isolated.”

“Or so the Order tells us,” the warman murmured.

Emeric made the sign of the Star. “The evidence is all around us. The dead places, the ruins no one can approach because of the wasting death. Men grew too grand, too filled with self-love--and Sin and Cyb destroyed them. That is enough for men to believe.”

“Spoken like a true priest,” Glamiss said coldly. “Men destroyed the Empire, Emeric. Not devils.”

“My point precisely, Glamiss Warleader. What we call Sin and Cyb, the Adversaries, men once called Satan or Asmodeus or Nergal, or a thousand other lost names. But at bottom it was always man himself who brought down the wrath of the Star or God or Jehovah--”

Glamiss asked impatiently, “Did the men of the Empire know magic?”

Emeric raised his eyes, shaded, to the yellow star. “There is the Vyka sun, Glamiss. If it didn’t rise tomorrow, would that be magic? Sin and Cyb at work? Or would it simply be that some process was taking place that you, a man, did not understand? Magic begins where human knowledge leaves off. The line between the known and the unsuspected is different for every man in every time. Faith, on the other hand, is something quite different. Men live and die, learn and forget. But there is a God in the stars and He made the heavens. There is a psalm: ‘The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament showeth his handiwork. ‘ That is all. Men who understand that know that there is no ‘magic.’ Not of the sort you mean.”

“Science, then,” Glamiss pursued, using the forbidden word.

The priest signed himself. “It is now the will of God in the Star that men be kept from the temptations of science, Glamiss Warleader. It is best that they leave the old knowledge to the Order of Navigators who will share it in good time. Remember that Sin and Cyb are the Adversaries. They wait--always. If I have failed to convince you of this it is because I am a poor priest. I know my failings, friend. I am noble and consequently tend to be arrogant. I question too much. That is why I am here, a horseback chaplain, instead of doing God’s truest work as a pilot of starships.” He fell silent, sick with longing to be again on the bridge of a starcraft, a holy proof of God’s power and mercy, preserved by His goodness from the holocaust and entrusted to His holy Navigators.

Glamiss said, “Don’t misunderstand me, Nav Emeric. I have no desire to feel the fires of the Inquisition. As for the people of this valley, they are rebels. In Vara’s name, I’ll make them pay for that. But will you--in God’s name--deliver them to the stake if it turns out that they have stumbled onto bits of the old knowledge?”

“The Order Militant decides, not I alone,” Emeric said. “If there is Sin and Cyb in Trama, the sinners will receive the mercy of Talvas.”

At the mention of Talvas Hu Chien, Grand Master of all Navigators, even Glamiss made the sign of the Star. The terrifying old man held the lonely worlds of the Great Sky in a grip of fear and awe. He was Prime Inquisitor as well as Grand Master, the spiritual vicar of all men, Controller of Starships, Scourge of Warlocks and Witches, of Cyb and Sin. Under Talvas, the Order had become the Order Militant. A scattered priesthood of men who piloted starships had become the supranational church of all the lands that once comprised the provinces of the Empire.

Emeric thought of the great, shadowed bays of the starships he had traveled in: vaulted and groined ceilings lost in the darkness overhead, men and horses jammed into the humming metal chambers surrounded by flickering torches and the smell of war. Emeric, as a Navigator, had known the open bridges of the holy craft. He had seen the mysteries of the shifting stars, the glory of open space--the Great Sky. The starships had been built by the men of the Empire. They were eternal, almost as holy as the Stars themselves. In a universe where such things could exist, there could probably be magic, as well, and a need for inquisitors.

He raised his eyes to the ice-bound mountains rising above the valley. One heard rumors in Vara that there were unholy things in those mountains, and that this was the reason the simple people of Trama had failed to send their tribute to the lord of their lands. Even the troopers murmured and listened to the rumors of a warlock--The Warlock--who had poisoned the hearts of the weyrherds of Trama against their rightful lord.

Ulm of Vara-Vyka was little better than a brute: a stinking animal of a man. But he was lord of these lands and it was the duty of his captains to enforce his rights and privileges. As a warleader of the Vykan warband, Glamiss would perform his duty. No more, no less. Rebels to the flail and sword. Still, Glamiss could remember his own beginnings, and it was a bitter thing to savage poor people one understood so well.

He crossed his arms over his dagger and flail and squinted speculatively at the westering Vyka sun. Half the day was gone; it would be night before the troop could reach the floor of the valley and build a fortified camp. It would be better, perhaps, to bivouac here on the ridge and test the valley people tomorrow. Besides, there was something threatening about the eagles of Trama, something more than the memory of rumors of magically controlled animals. If the birds were truly bewitched and chose to defend the valley, he would have to go carefully. It would not do to be defeated now. Glamiss was a young man with ambitions, and his plans did not include a check at the hands of peasants and ensorcelled birds.

He called to a trooper, who stumbled across the rough ground with the ill-temper of the habitually mounted man. Glamiss instructed that a camp be built and that the game, killed earlier in the lower valleys, be butchered and divided among the war mares.

When the warman had gone he turned again to the valley and the mountains beyond, trying to sense their mystery. In a short time he would call the Vulk to him and use his powers, and he would discuss his plans with Emeric, who was a gallant warman as well as a priest. But for the moment his thoughts were his own and he would keep them so.

For some reason he could not fully fathom, he felt on the edge of a great change in his life. He would not always be a mercenary captain for men such as Ulm, the lord of Vara. In some way that he did not understand, yet with complete certainty, he knew that one day he would rule his own lands. That was an absurd thought for a penniless soldier, yet he was convinced of it. The moment would somehow come and he would seize it. Men followed him willingly, and yet that was not the reason for his certainty. It was something deeper, more instinctive. Mystical, Emeric called it. Glamiss smiled to himself. The noble Rhad sensed it and, being more a man of intellect than was Glamiss, perhaps understood it better. “You are a born ruler, Glamiss,” he had once said. “What a pity you have no country.”

And Glamiss had then almost told his friend of the dream--that dream he had had since childhood, of himself standing astride an island between two broad rivers, with hundreds of starships in the sky and a glittering host behind him. He had a starred crown on his head, a feathered cloak on his shoulders, and a flail and dagger of gold in his hands. What a fantasy that was, he thought, yet how right it seemed. And what a sour disappointment to wake in the cold stone barracks and see the pale, distant stars shining through the unglazed windows on a bleak and primitive land nearly empty under the dark sky.

Where were the armies? Where the feathered regalia of a star king? Where the armada of starships?

It wi

ll come, he thought. It will come.

And if the destruction of the valley of Trama and its people was one small part of the cost, he would pay it. Regretfully, but he would pay it.

Chapter Two

The Rhadan warlock Cavour (Early Second Empire period) once suggested that starships could attain velocities in excess of 200,000 kilometers per standard hour. Not only did he run the fatal risk of the displeasure of the Order of Navigators by these calculations (in an earlier age he would have been burned), but he earned the derision of his contemporaries. His computations, based on the known elapsed time for flight between the Rimworlds and Earth, resulted in a hypothetical diameter for the galaxy of 12,800,000 kilometers. Even Cavour, a learned man for his day, was shaken by this immense figure, and recanted.

Interregnal investigators, such few as there were, believed that a figure of 666,666 kilometers represented the exact diameter of what they called “The Great Sky.”

--Matthias ben Mullerium, The History of the Rhadan Republic,

Late Second Stellar Empire period

--and for the treatment of certain as-yet-unconquered diseases, cryonic storage offers the best hope. It is not too fantastic to imagine a man of the future, suffering from cancer, leukemia, or some other illness, spending ten, twenty, or even a thousand years in low-temperature suspended animation waiting for medical science to solve his particular problem. It is even possible that atomic-powered, fully automated facilities could awaken a given patient when the computer in charge decided that sufficient time had elapsed, or when further cold-storage might irreparably damage the patient’s tissues. What a magnificent awakening! To open one’s eyes and see the World of the Future! Great, teeming, clean cities; vistas of--

--Dawn Age fragment discovered at Tel-Manhat, Earth,

in the Late Second Stellar Empire period

The Warlock of Rhada

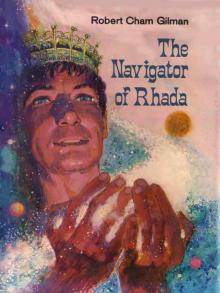

The Warlock of Rhada The Navigator of Rhada

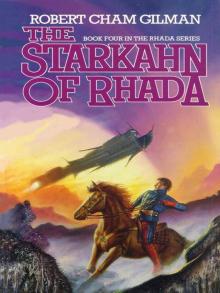

The Navigator of Rhada The Starkahn of Rhada

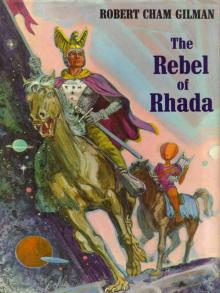

The Starkahn of Rhada The Rebel of Rhada

The Rebel of Rhada