- Home

- Robert Cham Gilman

The Rebel of Rhada Page 2

The Rebel of Rhada Read online

Page 2

“I said, ‘Tell me,’ “ Kier said sternly.

“You were remembering a reedy girl who loved you on Karma. A great personage. The daughter of a mighty king.” The Vulk strummed another chord and let it die away.

“Ariane.”

“The very same,” Gret said.

Kier laughed. The daughter of Glamiss had been thirteen years old the year the Battle of Karma was fought and even then betrothed to the star king of Fomalhaut, a lord of the Inner Marches, old and rich in men and worlds.

But no news of an Imperial marriage had reached the Rim worlds. Mariana, the Empress-Consort, wanted no Princess Royal with the resources of twenty worlds at her back.

Where was Ariane now, Kier wondered. She would be seventeen--no, almost nineteen now.

“The song,” the warleader said. “I don’t know it.” “It was written by a man of your own race, King.”

“A Rhadan?”

“Oh, no. There were no men on Rhada in this poet’s time. Would you believe me if I told you he lived eleven thousand years ago?”

Kier smiled and shook his head. Vulks, he thought tolerantly. They spoke in parables and riddles. Everyone knew the first men were created by God 6,606 years before the founding of the First Stellar Empire.

“A man of the Golden Age, then?”

The Vulk said, “One who lived before the Golden Age, before the first human being left the Earth. His name was Donne.”

“And how do you know that, Gret?” The Vulk played a delicate tune on a single string. “What is good is remembered, King.”

Kier would have liked to hear more of this poet who Gret claimed lived so long ago, but at this moment his cousin, the Navigator Kalin, entered and saluted him.

“We will make our planetfall in five hours, cousin,” the Navigator said.

Kier made the sign of the Star and murmured, as required, “God be praised.”

“Blessed be the name of God,” Kalin responded. Then he smiled at the warleader. Kalin thoroughly approved of Kier. He was courageous, properly noble, and devout in his observances. A fit descendant of the finest of the Rhad, the beatified Emeric.

Kalin, who was a generous-minded and rather simple young man, knew himself to be a good priest-Navigator, though, he often told himself regretfully, not destined to be a great one. The Rhad family had produced one outstanding religious only, and this was Emeric, who had risen to the rank of Grand Master of Navigators a generation ago to lead the Order into a new age of enlightenment. Probably Emeric, Kalin thought, would approve of the second star king of Rhada, too.

Emeric had believed, as had Glamiss the Magnificent, that men should recover all that they had lost in the Black Age. He had even dared to suggest that the time might come when a united mankind might have to face unspecified dangers from outside the galaxy, for he believed that the men of the First Stellar Empire had established, and then lost contact with, colonies in the Lesser Magellanic Cloud. Such a thing seemed inconceivable to Kalin. But if Emeric had believed it, then it was not to be thought impossible.

“Gret was telling me,” Kier said to his cousin, “of a singer of songs who lived--how long ago, Gret?”

“Eleven thousand years, King. Give or take a century or two,” the Vulk said.

Kalin frowned at the Vulk. The dogma stated very clearly that life began 6,606 years before the founding of the Empire. Gret should not tell such fairy stories. They were dangerously near to heresy, though there were warlocks nowadays who disputed the dogma. It was all confusing to Kalin, who had taken only the barest requirements in theology, preferring to specialize in studies more relevant to his primary duty as Spiritual and Temporal Guide of Starships.

“Well, eleven thousand or not, Gret, it was a fine song. You shall play it tonight at dinner for our Navigator and make his shaky theology totter. But not this moment.” He addressed himself to his cousin and said, “Send an orderly to collect Cavour and Nevus. If we are to reach Nyor in five hours, we have plans to make.”

“Will there be ceremonies, Kier?” Kalin asked. “I have brought my finest robe and cowl. I thought it wise.”

Kier put an arm across his cousin’s shoulders. “I hope you have brought your largest war horse and sharpest weapons. There may be ceremonies of a sort we don’t anticipate.”

The Navigator looked perplexed. “Are we in danger?”

“I hope not, Kalin,” Kier said.

“We are, though. You think so.”

Kier half smiled. “It is the way of things in this time, cousin.”

“But we have warmen,” Kalin said, adjusting to the idea of danger.

“Only enough to hold the starship if we are attacked. More would have looked like rebellion.”

“But Kier--on Earth? Why would anyone trouble us? Isn’t this a state visit--?” He broke off, feeling frustratingly naive and innocent. He looked at his warrior cousin for explanation. “I mean, Kier, I know things have changed since The Magnifico’s time, but the Imperials would never dare--” He stopped, suddenly aware that he was in no way sure what, exactly, the Imperials would dare, or even why.

“Find me Cavour and Nevus,” Kier said. “Then join us here. I want you to hear what is said. A holy Navigator you may be, but you’re a Rhad, too. If there is trouble, I want you to know what to do.”

“As you command, King,” Kalin said with sudden, grave formality.

Gret’s eyeless face grew somber as the Navigator went. He began to play on the strings, making mournful and non-human melodies that only brushed the senses.

“To be so young,” he said murmuringly, “to be so innocent and to go into such danger. It is sad, King.”

Kier’s eyes narrowed. “What danger, Gret?”

“We know. Both of us know.” The music wove a strange and age-old pattern in the way of Vulk laments. “Sarissa,” the fool said. The sibilant name seemed to mingle with the dirge.

Kier laid a hand across the strings and stopped the music in midflight. “What do you know about Sarissa, Gret?”

The Vulk shrugged, a human gesture Kier would understand. But what did the motion mean to Gret, Kier wondered.

“I know what there is to know,” the Vulk said. “I know that the star kings of the Rim worlds gather there. There is talk of rebellion and war against the Empire.”

“The redress of grievances, Gret,” Kier said in a hard voice.

The Vulk shook his head in denial. “Rebellion, King. And we Vulks remember the Black Age, the time of darkness, the centuries of war and death between the Empires.” He struck a deep, resonant note. “Rebellion, King. Your father would weep.”

“How do you know of this?” Kier spoke harshly.

“Vulks know. And this, too, I know--that you are undecided and that you will try to buy relief from Torquas for Rhada with a renewed pledge of loyalty.”

“Landro, Mariana, and the Imperials are bleeding us white, Gret. Military service is all the Rhad have to offer --and it was always enough in Glamiss’s time. Now they demand goods and money we do not have. I have complained so that I’ve been summoned to answer for it.” Kier stood and held his sheathed sword in both clenched fists. “I love the Empire, Gret, as my father before me loved it. But I am a Rhad of Rhada--”

“The star king is father to his people,” Gret said with Vulk formality.

“Will Mariana accept my terms?” There was no more talk of Torquas. Both Vulk and man knew where the power lay.

“This I do not know, King. But you are putting yourself into great danger to make terms without armed men in plenty behind you.”

“I know they call me The Rebel,” the young star king said. “But I cannot call on The Magnifico’s son with an army. On Karma the Emperor was more than my general; he was like a father.” He drew the great sword halfway from its sheath and looked at the glistening blue god-metal of the blade. “I had this from his own hand, Gret.” Gently, he sheathed the blade. “No, I had no choice. I had to come alone.”

The Vulk

bowed his head and struck the strings. He did not say that Kier was not alone and that, if he was taken, all aboard this starship would die. That was the way of things in this time. Everyone aboard this starship belonged to the star king. It was fitting.

He struck the strings again. “When the history of the Rhad is written, King,” he said, “and when all the battles are songs”--he lifted his blind face to the young man and smiled--”men will search time, from the age of cybs and demons to the hour we call now. And you will be remembered as the greatest of all the Rhad. Greater than Aaron the Devil, greater even than the holy Emeric. If--” He paused and suddenly drew a flurry of savage and martial sounds from the delicate heart of the lyre. “If you are alive tomorrow, King.”

2

--biochemical interactions to be kept rigidly within the prescribed parameters because, without exact control, the DNA molecules will be unstable and the life sequence will fail to become self-sustaining.

Extremely high-power requirements demand that any ex--

Golden Age fragment found at Sardis, Sarissa

Blood of the child, salts of the ground

Give pain with the power and listen for sound

Pray now to sin

To let life begin

A heartbeat inside

Or the old ones have lied.

From the Book of Warls, Interregnal period

The leather-armored patrolmen walked in pairs in this quarter of the city; the light of their poled lantern cast a yellow light on the damp stone of the walls, so that they went in a pool of brightness that married the gloom of Sarissa’s perpetual dusk.

In the rotting buildings, the poor of Sardis lived in squalor. A few of the more enterprising entertained the warmen on leave who were Sarissa’s only visitors, and as the patrolmen went, they could hear the sounds of shrill laughter, strains of rasping music, and the occasional cry of alarm of some drugged or drunken warman awakened to his peril too late.

The patrolmen paid no attention to these sounds of lawlessness. They were accustomed to them, and they had no desire to remain near the house of the warlock on the Street of Night.

The warlock’s name was Kelber, and it was known that he lived under the protection of the new warleader of Sarissa, Tallan. But even without the warleader’s contemptuous protection, no patrolman would have disturbed the old warlock at his mysterious, sinful work. No Sarissan passed the crumbling stone house on the Street of Night without a thrill of superstitious horror and the sign of the Star in the air to ward off the warlock’s familiar devils.

So the patrolmen, with unknowing irony, called the All’s Well and passed swiftly by. And within the house the cry went unheard, for the walls were meters thick. For a thousand years no house had been built on Sarissa that was not a fortress. The planet had a dark and bloody history, with a succession of savage kings and warleaders of which Tallan, called The Unknown because no man knew from whence he came, was only the most recent.

The warlock’s workshop lay at the back of the stronghold, near a warren of storerooms that had once held weapons and food. The walls were crusted with white salts, for the house backed against the vast desolation of the Great Terminator Marsh, a bog that covered most of the land area of the planet’s single continent.

Few Sarissans realized the extent of this immense marsh. Indeed, few Sarissans knew that their world was a sphere, an astronomical anomaly: the single planet of a dull red star.

There was no sky on Sarissa. The cloud layer lay at ten thousand meters. In three thousand years, since the planet was first occupied by men, the clouds had never parted.

The oxygen content of the air was low, and Sarissa had bred a brutish race of savage, slow-witted men from the original colonists who had come here, for God knew what reason, in the last years of the Golden Age.

Within the old warlock’s laboratory, the walls were damp and the air cold. Strange, ancient machines crowded the floor. Books and fragments of old manuscripts were piled on tables and benches. Stuffed creatures from half a dozen worlds hung grotesquely from the vaulted ceiling. The room had a smell of age and decay.

It could have been the workshop of any witch or warlock anywhere in the Empire, except that it was not lit with lamps or torches but by electricity.

Heavy cables, the insulation checked and worn, snaked about the floor, eventually to vanish into one of the storerooms. This chamber was filled, from wall to wall and floor to ceiling, with an astonishing collection of storage cells, batteries of every shape and size, scavenged by Kelber from half a hundred ancient mounds and ruins. The battered machines powered by this tangle of cables and batteries all carried the ancient Star blazon of the legendary First Stellar Empire. Magical devices, they were, built by the god-men of the Golden Age.

Even with Tallan’s tolerance, the patrolmen would not have spared this room or its contents had they the courage to investigate it. In dread and panic, they would have put the old man to the sword and the house to the torch. Sin, the terrible power of darkness that had destroyed the Golden Age, was everywhere. But no patrolman had troubled Kelber since the new star king began to rule; besides, the old warlock was failing and growing feeble and half mad with age and disappointment.

He crouched over a worktable now, consulting an ancient book, shaking his head and talking to himself. He limped from the book to one of the machines and made an adjustment with gnarled, arthritic hands.

He was gray-bearded and dirty. He could not remember when he had last eaten, nor did he care.

He wormed his way through the clutter to a half-formed, almost human thing sprouting wires and tubes that lay on a metal frame in the center of the room.

He turned an hourglass and mended a broken connection, chittering and mumbling to himself. When he had done, he shuffled to a control panel and closed a switch, and immediately some of the ancient machines began to hum and the air filled with an acrid smell of burning.

The man-thing on the rack twitched and shuddered and then lay still, its flesh bubbling where the wires entered.

The warlock dashed the hourglass against the wall in a fury. He trembled with demented anger, bobbing up and down, trying to remember, muttering old chants from the Book of Warls, the black bible of warlocks. But it was useless, useless. Why couldn’t he remember? How had he grown so old, so forgetful--?

From the dark doorway came the sound of laughter, contemptuous and cold. “Another failure, Grandfather.”

The old man returned to his desk and began rooting like an animal in the piled confusion of papers.

“Back to the Warls, is it?” The speaker stepped into the light. He was a large man, immensely strong, proportioned with a powerful grace that no Sarissan could hope to match. He wore a dark cloak and cowl.

The warlock frowned and said crossly, “Power is what I need. Power. I used it and it is gone! How did the ancients do it, how? Where did the new life in the batteries come from? Where did they find it?”

“Try chanting, Grandfather,” the cloaked man said ironically, turning back his cowl.

His face was inhumanly handsome, lofty, noble. Only the old warlock knew that it was the face of an actor of the Golden Age, a man four thousand years dead, and the warlock had forgotten.

“I did it once,” the old man said with the stubborn anger of age.

“A miracle,” the large man said with sarcastic piety. He made the sign of the Star mockingly. He unfastened his cloak and thrust it back to hang from his broad shoulders. The bright light glittered on the ornamented war harness of a star king. A great sword hung at his side, the pommel carved with the royal mark of Sarissa.

“They could help me,” the warlock said querulously. “By the Star, they should help me--”

“Don’t swear by the Star, Kelber,” the star king said with mock sadness. “You’ll be struck down.” His cold eyes surveyed the clutter of forbidden machines. On Sarissa the mere possession of such engines of sin could mean death at the hands of a terrified mob. Perhaps, he

was thinking in his icy, methodical way, it would be simplest merely to call the patrolmen.

The old man sat, confused in his mind. His folded hands trembled. He was trying to remember. It seemed to him that things had not always been this way. It seemed to him only a short time ago he had been a robust man, a seeker after the old knowledge, a strong man with a searching mind, impatient with the laws and the timid questings of the Navigators. But what had happened, he wondered. Where did it all go? How did I forget? How did I grow old?

The star king stepped to the center of the room and looked down at the incomplete thing on the rack. He prodded it with a booted foot. The wires trembled. There was no sign of life. He turned to look speculatively at Kelber. “What were your plans for this, I wonder.”

The warlock rubbed his bony hands across his face and frowned. “Plans? What plans? I don’t understand you.”

“Three years ago you were told there was no need for this cyborg. Energy weapons are what’re wanted. But you wasted your time on this--thing.”

The old man grew suddenly very angry. “You--you and this thing, as you call it, are the same, Tallan. You remember that.”

The star king shook his head. “You are old, Grandfather. You grow senile. You imagine things. How could such a thing be?” The mouth smiled, but the eyes remained cold, watchful.

The warlock shook his head and blinked his tired eyes. “Tallan. You remember. You must remember--”

Again, that slow and contemptuous shake of the head. “You only imagine it happened that way, old one. I am Sarissa--a star king. How could what you say be true?”

“Here, Tallan,” the old man said pleadingly. “Here in this workshop--”

“No.”

“Tallan?” A puzzled twist of the head.

“I said that you imagined it, Grandfather. I let you imagine it because it amused me. But tonight it does not amuse me.”

Kelber felt his old heart flutter. He suddenly realized his danger.

Tallan said, “I warned Landro that you were an old fool. I told him that he would get no weapons from you.” He smiled grimly. “You know only the Book of Warls, and there are no weapons there.”

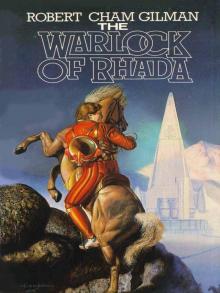

The Warlock of Rhada

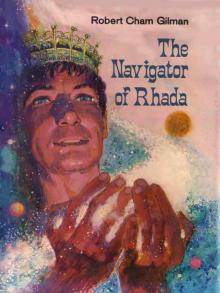

The Warlock of Rhada The Navigator of Rhada

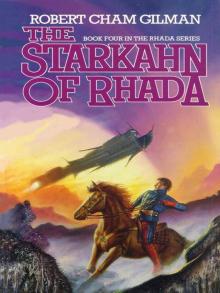

The Navigator of Rhada The Starkahn of Rhada

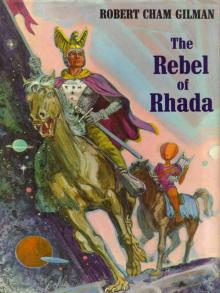

The Starkahn of Rhada The Rebel of Rhada

The Rebel of Rhada